by Alex Brant - Monday, February 26, 2018

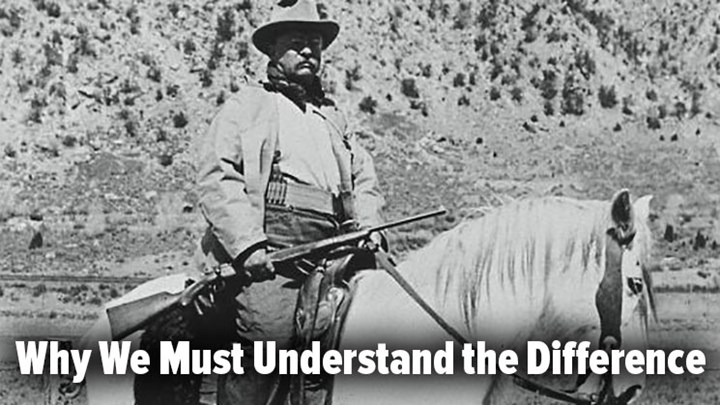

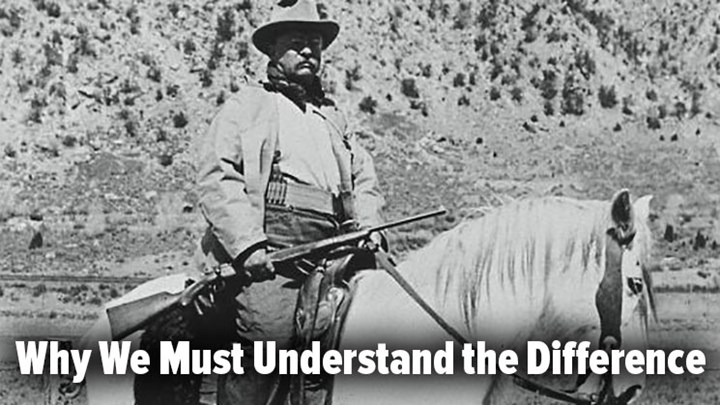

*Pictured above: 26th U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt—the "conservationist president" (1858-1919)

President Theodore Roosevelt was a hunter-conservationist and NRA member who used his office to protect and conserve the country's natural resources to be used and enjoyed by future generations. His chief advisor and ally was Gifford Pinchot, an avid hunter who is generally credited with coining the term conservationist. Roosevelt federally protected 230 million acres during his presidency. God bless him. Roosevelt secured more federal land from potential development than all previous presidents combined.

For some background, during the environmental movement of the early 20th century, two opposing groups emerged: conservationists and preservationists. Conservationists wanted to regulate human use while preservationists wanted to eliminate human impact completely. The National Park Service (NPS) website states, “Conservation and preservation are closely linked and may indeed seem to mean the same thing. Both terms involve a degree of protection, but how that is protection is carried out is the key difference. Conservation is generally associated with the protection of natural resources, while preservation is associated with the protection of buildings, objects and landscapes. Put simply, conservation seeks the proper use of nature, while preservation seeks protection of nature from use.”

As I write this I am in Cape Town, South Africa, having just finished a 24-day safari in Zimbabwe’s Savé Valley Conservancy. During this time, I was hunting leopard. While some preservationists give lip service to protecting the big cats, I was offering room service. We had 15 cats feeding, not including a few cubs—nine were female, six were male. Of the six males, one was big enough to shoot but was only three or four years old which made shooting him illegal. While he was between 150 and 160 pounds, it was too soon to take him out of the gene pool. I left without firing a shot.

Interestingly, in late July 2015 I was approached by Natasa Simovic of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) to appear on the network’s daily show “Global with Matthew Amroliwala” to discuss hunting. She wanted me to come to New York City the next day but I had other obligations and couldn’t be there until the next week. She replied that it would be too late, noting that the story they wanted to report on would have lost traction. She was wrong.

A few months later, I was approached by two documentary producers for the BBC—Katie Churcher and Alexandra Lee. They were beginning to work on a documentary about hunting and wanted to cover both the pro-hunting and anti-hunting platforms. I was to be the pro-hunting voice. They had been given my name as an ethical hunter who believed in and practiced fair chase and wanted to join me in South Africa to film me hunting a lion. With almost everything in place, they came to New York to turkey hunt with me to get some footage and background on my hunting views prior to the trip.

One thing that surprised me was that almost without exception, none of the pro-hunting groups, clubs and organizations wanted to get involved. I had planned on bringing another film crew along to ensure the BBC wouldn’t bury me through unfair editing and hoped to get support for a film crew from a number of high profile associations but all were scared of the potential backlash. In the end, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) stopped issuing lion import permits while they studied the lion hunting scenario in South Africa in more detail. Catch 22: While I was one of the first hunters to receive a CITES import permit during this period of review, by time that occurred, South Africa had stopped issuing hunting licenses for lions. Putting it off for another year no longer appealed to the BBC and for that I could not fault them.

What I found most interesting was the conversation between the reporter and myself in regard to the ethics of hunting, which was filmed in my office. I was explaining how hunting benefits local communities and economies, especially in a place like Africa where poverty is the rule, and often adds legally obtained food for local communities. Without that, poaching, which is a current problem and has been for a long time, gets exacerbated. I explained that unknown to most, according to the National Park Service, “one of the largest conservation organizations in the world, the World Wildlife Fund, was created in 1961 to protect large spaces for wildlife conservation. Conservation generally follows an economic motive; in this case wildlife preserves in Africa during the dissolution of the British Empire in the late 1940s to ensure big game hunting remained commercially viable.”

Continuing, I was making the point that taking an old elephant out of the herd—one on his last set of teeth—both gives him as humane a death as possible in Africa while feeding an entire village. I stated that the harvest of an individual elephant benefits the herd—especially in areas where numbers exceed the carrying capacity, causing a boom-and-bust cycle that not only affects their numbers but other species as well. Elephants rip down trees and change habitat dramatically when their numbers exceed their carrying capacity, as undoubtedly is the case in Botswana now that hunting is not permitted.

The reporter replied stating, “Conservationists would disagree with you.”

“I beg your pardon?” I said.

He repeated it.

“The way you are using the term ‘conservationist’ is a misnomer,” I pointed out. “The term ‘conservationist’ is generally acknowledged as being coined by Gifford Pinchot, an avid hunter who worked for TR.”

I stated that what the reporter meant to say was that preservationists would disagree with me as the difference between a conservationist and preservationist is huge. I went on to explain that hunters were the original conservationists and are still the best. Organizations such as Ducks Unlimited (DU) have saved millions of acres of wetlands and breeding grounds for wildfowl. Hunters’ dollars fund conservation programs across the entire country. This may be done directly through hunting licenses or indirectly through the purchasing of rifles and shotguns. Even the years when I'm not in the United States for the duck hunting season, I will buy my license and duck stamp simply to support conservation projects.

Hunters have never driven game toward extinction. Today's threats in Africa are due to the outrageous and illegal demand—mostly from the Far East—for rhino horn, ivory and lion body parts now that tigers are in such short supply. Simultaneously, poachers put out wire snares hoping to kill antelope but occasionally—actually all too frequently—injure Cape buffalo, making them extremely dangerous.

I was in a concession in the north of Kruger National Park last September when we came across a buffalo with a snare around its neck. I wanted to shoot it and put it out of its misery but was told it was not possible. I asked the game ranger if he could do it and was told “no.” This particular buffalo didn’t pose danger to anyone, and there were villagers in the vicinity. There was a certain poetic justice to end the incident. We found out the next day that the poacher had come back to check his snare armed with a spear, hoping to find an antelope in it. When he approached, the buffalo was so enraged that he broke the wire snare from the tree, gored the fellow and continued on his way. Amazingly, while he had a spear in one hand he had a cell phone in the other. There was cellular service and he was able to call for help, but by time it arrived he had bled out. This was justice in the bush.

Instead of attacking hunters—the true conservationists who make animals important because they add economic value to the community—preservationists should focus on attacking the corrupt officials, both governmental and fellows who work at ports where illegal ivory and rhino horn get shipped to China. What would really protect African animals, in addition to hunting, would be eradicating the demand for these illegal products in the Far East.

A final thought: Most preservationists are completely hypocritical. Most have no compunction in eating beef and chicken or wearing leather shoes and jackets. They simply don’t like the fact that we enjoy and protect the outdoors in a way that doesn't coincide with their Walt Disney version of the world.

E-mail your comments/questions about this site to:

[email protected]