by Keith Crowley - Monday, June 25, 2018

The name George Armstrong Custer still can start an argument even 142 years after his famous death on a Montana hillside on June 25, 1876. He was one of this country’s most controversial historical figures for good reason. He was a complicated man, full of contradictions—and ego. Love him or hate him, whether he was facing J.E.B. Stuart at Gettysburg or Sitting Bull at the Little Big Horn, he is unforgettable. However, as much as we think we know about him, Custer had a few lesser-known sides to his complex personality.

For one thing, Custer truly loved hunting. During his early days on the western prairies he began writing letters under the pseudonym “Nomad” to a sporting magazine of the day, Turf, Field and Farm. Between 1867 and 1875 he wrote 15 stories for the magazine recounting his adventures in the West. He also included many hunting tales in his memoir, “My Life on the Plains,” and in the hundreds of letters he wrote home.

An officer’s life on the prairie was often the picture of boredom. Despite the military mission, there was little time spent actually fighting Indians. While the foot soldiers and teamsters attached to a given unit had multiple jobs to do, the officer class enjoyed leisure time. Writing was one diversion for Custer, and hunting was an outlet for his pent-up energy.

Custer believed hunting was a practical preoccupation for everyone in camp, officer or enlisted man. Game also was a critically important food source for a perpetually hungry army. And, according to Custer, useful military skills were acquired through the hunt:

“To break the monotony and give horses and men exercise, buffalo hunts were organized, in which officers and men joined heartily. I know of no better drill for perfecting men in the use of firearms on horseback, and thoroughly accustoming them to the saddle, than buffalo-hunting over a moderately rough country.”

In those pre-settlement days the West was full of game, so Custer and his men took advantage of the situation:

“Our table fairly groaned under the load of choice game daily heaped upon it. … Beginning at buffalo as the largest, we had buffalo, elk, black-tail deer, antelope, turkey, geese, duck, quail and several variety of snipe…”

On his way back to Fort Lincoln from the 1873 Yellowstone expedition, Custer killed multiple elk, including “a fine large buck-elk taller than Dandy (his horse) weighing, cleaned, 800 pounds, and with the handsomest set of antlers I ever saw… .”

Custer also was a talented taxidermist who often worked by lamplight into the night preserving one of the day’s take while the rest of the camp slept. He once wrote to his wife, Libby, “I have succeeded so well in taxidermy that I can take the head and neck of an antelope, fresh from the body, and in two hours have it fully ready for preservation.”

Custer also was a talented taxidermist who often worked by lamplight into the night preserving one of the day’s take while the rest of the camp slept. He once wrote to his wife, Libby, “I have succeeded so well in taxidermy that I can take the head and neck of an antelope, fresh from the body, and in two hours have it fully ready for preservation.”

He also claimed to be one of the first taxidermists to mount an entire elk body for display. Since he didn’t have room for such a large trophy, he donated it to the Audubon Club in Detroit.

Custer was also a bit of a braggart regarding his skill with a rifle. One reporter wrote that he was “always telling of the good shooting he had done.” In a letter to Libby he himself stated, "I have done some of the most remarkable shooting ... it is admitted to be such by all."

In a “Nomad” story from October 1873, Custer states, “I seldom killed [antelope] at a less distance than 150 yards, running up from that distance to 630 yards… .”

Now 630 yards is a long shot considering his hunting rifle of choice was the historical Remington Rolling Block in .50-70, using black powder.

Custer’s boastful tendency was a repeated occurrence, but apparently his opinion wasn’t shared by everyone. Well-known scout Luther North and famed naturalist George Bird Grinnell both joined Custer on the 1874 Black Hills Expedition, and each remained unimpressed by the General’s prowess.

Grinnell wrote that “Custer did no shooting that was notable. It was observed that, though he enjoyed telling of the remarkable shots that he himself commonly made, he did not seem greatly interested in the shooting done by other people.”

In his memoir, Man of the Plains, North recalls a day when he exhibited some fine marksmanship in taking three running deer at 100 yards. Grinnell brought one of the animals to Custer’s tent. Custer’s reply: “Huh, I found two more horned toads today.”

Custer’s two most famous hunts by far revolved around the most iconic species of the West: the American bison, which Custer called “buffalo.”

The first happened on one of his official outings as he often was called upon to guide European dignitaries out West. In January 1872, President Ulysses Grant and General Phil Sheridan arranged for a buffalo hunt for Russian Grand Duke Alexis. Sheridan chose Custer as the grand marshal and William “Buffalo Bill” Cody as the chief guide. The Nebraska hunt site was selected with the help of Native Americans. Alexis ultimately emptied his revolver on the buffalo then had to borrow Cody’s famous buffalo gun, a .50-70 Springfield Allin Conversion that Cody named “Lucretia Borgia.”

While Cody, also a world class self-promoter, barely mentions Custer in his diary, there are photos of Custer, Alexis and Cody together. Custer wore fringed buckskin and a sealskin hat so even if he wasn’t the most important person on that hunt, he looked the part.

In the second story Custer was front and center. It also proves he could be reckless to a fault.

He wrote the story for Turf, Field & Farm on Sept. 9, 1887, and later included it in his book “My Life on the Plains” (which another 7th Cavalry officer disparagingly called “My Lie on the Plains”). Custer starts the book version with an unusual admission, saying, “Here I will refer to an incident entirely personal, which came very near costing me my life.” It was out of character for him to admit human failings.

This hunt was during Custer’s first western campaign and he was riding ahead of his column on his favorite thoroughbred, Custis Lee, in Kansas. With him were five of his omnipresent dogs: greyhounds Fanny, Rattler, Sharp, Lu and Rover. When Custer spotted a herd of antelope, the chase was on, with the General on his horse bringing up the rear. Not even the fleet-footed greyhounds could match an antelope’s blazing speed.

By Custer’s account, “We were then in a magnificent game country, buffalo, antelope, and smaller game being in abundance on all sides of us. … I had several fine English greyhounds, whose speed I was anxious to test with that of the antelope, said to be—which I believe—the fleetest of animals.”

Inevitably the dogs lost the antelope. Then Custer spotted a bull buffalo—his first opportunity to hunt the largest game on the plains.

Custer forged ahead, catching up with the bull after a 3-mile pursuit. As he went to shoot, the buffalo veered into the horse, causing Custer to fire his revolver into Custis Lee’s head. The horse died instantly, catapulting Custer onto the prairie. Custer was alone with his dogs, miles from his command and with no idea where he or anyone was, later noting “Indians were liable to pounce upon me at any moment.”

He finally saw a dust cloud approaching he saw the Cavalry guidon, or pennant, flying over the approaching column—Custer’s famous luck.

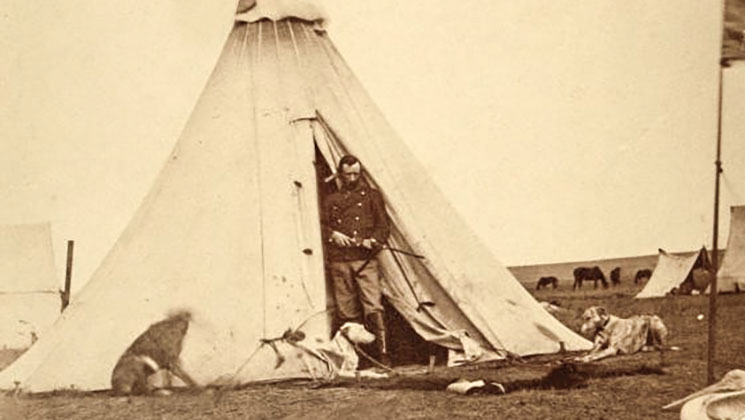

Say what you will about him but Custer truly loved his hunting dogs. In numerous field photos he has several devoted dogs at his heels. When Maida, one of his favorites, was killed during a buffalo hunt in 1869, Custer wrote a poignant poem about her:

Poor Maida, in life the firmest friend,

The first to welcome, foremost to defend;

Whose honest heart is still your master's own,

Who labors, fights, lives, breathes for him alone.

But who with me shall hold thy former place,

Thine image what new friendship can efface.

Best of thy kind adieu!

The frantic deed which laid thee low

This heart shall ever rue.

But Custer’s pets were not sacrosanct. During the famous 1868 Battle of the Washita, the campaign that made his name as an “Indian fighter,” Custer had all the dogs following the command, including some of his own, muzzled and killed so they would not bark and alert Black Kettle’s camp that soldiers were approaching.

It comes as no surprise that Custer also loved horses. Some of his “Nomad” letters mention his affection for Kentucky thoroughbreds, yet he frequently had horses killed during military campaigns. A pragmatic military man, he had no issue with sacrificing animals, even beloved pets, to gain a strategic advantage or defend a command. But that didn’t mean he was heartless.

Custer had a pack of his faithful hunting dogs along on that fateful day at the Little Bighorn. He wrote a letter to Libby shortly before the battle, noting, "Tuck regularly comes when I am writing, and lays her head on the desk, rooting up my hand with her long nose until I consent to stop and notice her. She and Swift, Lady and Kaiser sleep in my tent."

Custer’s cherished hunting dogs likely died with him on a hillside in Montana.

E-mail your comments/questions about this site to:

[email protected]