by Jim Heffelfinger - Friday, November 15, 2019

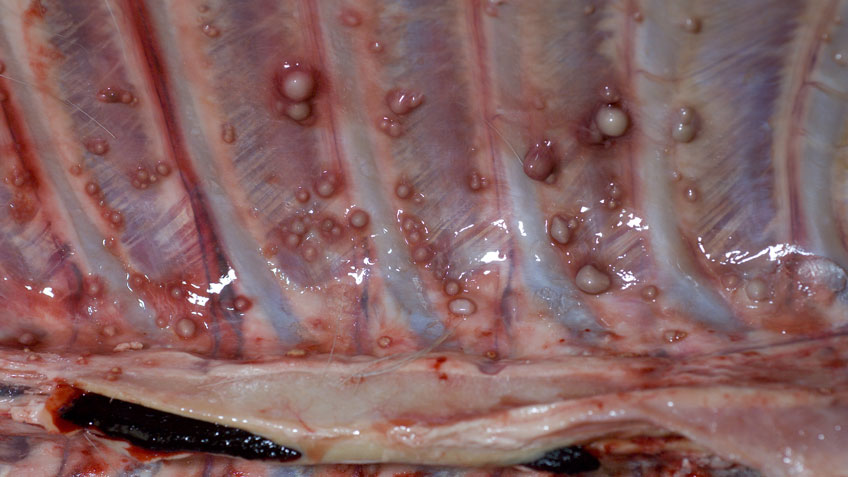

Bovine tuberculosis is caused by bacteria (Mycobacterium bovis) that is different from the one that causes common human tuberculosis (Mycobacterium tuberculosis) but the symptoms are the same: fever, coughing, chest pain, chills. The bovine version accounts for only about 2 percent of all human tuberculosis infections. Bovine TB has been nearly eradicated in cattle in the U.S., but it persists as a problem in wild white-tailed deer in a small area in the northeastern part of lower Michigan. TB shows up as small round nodules containing a cheese-like yellow pus, most commonly seen in the lung cavity. The nodules gradually enlarge and ultimately kill the animal.

Most human cases of bovine TB come from people consuming unpasteurized milk and other dairy products. However, it is possible for hunters to contract bovine TB from deer either by breathing in bacteria while field dressing or through a cut in the skin. In humans and cattle, it can be cured with antibiotics, but in a wild, free-ranging deer herd it is not possible to treat enough of the population. In some cases, an infected person may not become sick because the bacteria can lay dormant for years then reactivate later to cause tuberculosis. This makes it difficult to pinpoint the exact source of infection.

The Michigan situation is unusual because it is the only place in the nation where bovine TB is established and self-sustaining in a wild deer herd. In the 1920s, nearly a third of cattle in this area tested positive for bovine TB. In 1975 it was detected for the first time in a 4-year-old whitetail buck a hunter harvested and again in an old doe in 1994. Since humans can contract bovine TB, the inevitable happened in 2002 when a hunter apparently inhaled the bacteria while field dressing a deer and again in 2004 when another hunter cut his finger and contracted TB. The recent CDC report that ignited newspaper and Internet articles across the country was sparked by the 2017 diagnosis of bovine TB in a 77-year-old deer hunter in this same area. He was not in contact with all the usual sources of TB infections but had been in contact with, and had eaten, many whitetails in this area of Michigan over the previous 20 years. Genetic analysis indicated that the strain of TB the 2017 hunter was infected with was very closely related to a strain identified in 2007, indicating that he was infected at some point during his past deer-hunting activities and that the TB reactivated in 2017.

Even this Michigan focal area of bovine TB in whitetail deer is limited almost entirely to a small area consisting of a few counties that for decades had inappropriately high deer populations and a high density of feeding and bait stations that maintained the bovine disease in wild deer. To put things in perspective, testing this hotspot area in 2017 resulted in detecting the disease in only about 1.4 percent of deer. The documentation of only three human cases in this area in more than four decades of hunters field-dressing deer is a good illustration of just how unlikely one is to contract bovine TB from a deer.

However, even with the unlikely danger of contracting TB from deer, it is always a good idea to practice basic safety precautions when handling and field-dressing a deer if you are not certain where it has been. Here are a few suggestions to add to your normal routine.

With a very low prevalence of bovine TB (less than 2 percent) in one very localized deer population in Michigan, this is not something you need to be worried about on your deer hunt this year. Don’t get taken by overly enthusiastic reporters and click-bait artists. Obviously, if you are hunting in the small Michigan area with bovine TB, know the signs and symptoms of TB in deer and humans. But even in this Michigan hotspot where this disease has been known to exist in deer for four decades, thousands of deer have gone safely from field to freezer. Following the above recommendations will virtually eliminate the chance of you contracting TB on a deer hunt.

About the Author: Jim Heffelfinger is a certified wildlife biologist with wildlife degrees from University of Wisconsin—Stevens Point and Texas A&M University—Kingsville. He has worked for the U.S. government, state wildlife agencies, universities and the private sector. Jim is the author of “Deer of the Southwest,” in addition to authoring or coauthoring more than 200 magazine articles, 50 scientific papers, 20 book chapters and five TV scripts. He is a Boone & Crockett professional member, a full research scientist at University of Arizona, chairman of the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies’ Mule Deer Working Group representing 23 western states and Canadian provinces and wildlife science coordinator for the Arizona Game & Fish Department. He has received the Wallmo Award, given to the leading mule deer biologist in North America and the 2009 Professional of the Year award from the Mule Deer Foundation. Jim is also a member of the International Defensive Pistol Association and the U.S. Practical Shooting Association and competes weekly with his 1911.

Follow NRA Hunters' Leadership Forum on Twitter @HuntersLead.

E-mail your comments/questions about this site to:

[email protected]

Proudly supported by The NRA Foundation and Friends of NRA fundraising.