by Frank Miniter, Editor in Chief, America’s 1st Freedom - Friday, November 29, 2019

As sportsmen, we go back. We return to our old deer stands, to our duck blinds and upland haunts. We see these places change, year after year, and through the seasons. The fields, marshes and forests take on a special feel for us. They become a part of us. They are alive with memories, maybe of our fathers or brothers or pals who once upon a time went into them with us.

This is why we mourn when we lose a lease or when someone else gets access and puts a stand near our old spot. We are not just losing a great duck blind, deer stand or upland cover, we are losing a connection to old friends and loved ones. We are severed from memories of bucks coming down a rub line that always seemed to run down the same ridge or from sights of the ducks coming in heavy with winter at their backs.

As hunters, we get in tune not just with nature and the wildlife, but with the happenings within specific environments. We get in step with all that occurs on that marsh, upland cover, drainage or woodlot. This allows us to see when things are right and when they are not. This makes us an army of active conservationists watching over the fields, forests and waterways. This is why it was always natural for sportsmen to become the conservationists we are today.

I saw this again in October.

The Catskills Mountains in New York were all awash in color, as if an impressionist painter had splashed primary colors over the once green forest to create a surreal landscape, aesthetically expressing how a place feels. The oaks up high had lost their crimson leaves. Lower down, on the mountain benches, the leaves were mostly up in splashes of yellow and red. In the sequence of the hunter’s seasons, this was the right time to walk for grouse.

I parked on a dirt road covered with oak leaves and climbed the mountain to a bench where springs seep from the ground, loosening the earth, slowly toppling trees. This wet ground keeps meadows open and thickets tangled. Grapevines climb these trees and, eventually, strangle them to the wet ground. All of this creates splendid ruffed grouse habitat even in this otherwise maturing forest.

Every October I could always count on a dozen flushes on this mountain bench.

As I came down the bench this time, the habitat looked marvelous. It glowed with color and I saw piles of wild grapes on the ground near acorns, hickory nuts and more.

Despite looking like the ideal grouse location, there wasn’t a single bird in the top of the cover. I also didn’t hear a single grouse drumming.

The year before, after also not getting a single flush there, I thought it was all because of a poor grape crop. This year, there was autumn food for grouse everywhere, but still not a flush. It was like visiting a lovely little town and finding all the buildings and lawns mowed and stores full, but never seeing a single person on the streets or in the shops.

I looked, wondering, A down cycle?

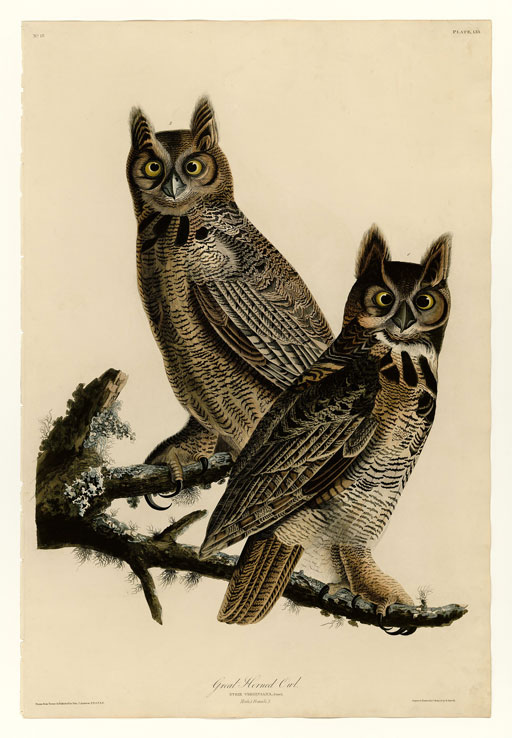

No, I found, it was more local, more basic, than that. I walked up on a huge great-horned owl sitting in the middle of the best habitat. He flew off the cover and landed in a tree above me on the ridge and started to hoot aggressively at my intrusion. I knew great-horned owls are grouse killers and so I knew what happened.

Each year that place always held about a dozen birds. Over the months that owl easily could have cleaned them out. I hated that owl for a moment, but then I shrugged and left. Nature is like this. It can be harsh. Sometimes predators sit on a resource until it is depleted. Nature TV specials won’t tell you that, but a lot of wildlife biologists have told me this.

I have other grouse haunts, but that one was special. I know where the central lek always was. I always left that drumming bird alone. Now it’s silent.

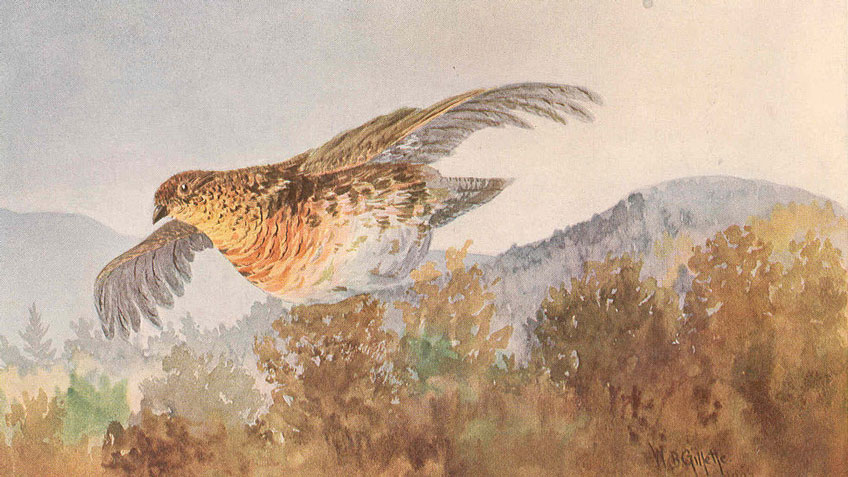

Still, I know that one day the grouse will be back there again and a grouse will drum again on that log. I will return. Until then, I’ll move on to other places in search of what to me is the symbol of the northern forests and mountains, the ruffled grouse with his tuft of feathers atop his head cocked the way men used to wear fedoras as he stands upon a log ready to drum his wings to declare to everyone within a mile that the place is his kingdom.

Lead Image: Plate 41 of "Birds of America" by John James Audubon depicts ruffed grouse.

About the Author: Frank Miniter, editor in chief of the NRA's America's 1st Freedom, has been writing about hunting issues, gun rights and more for the NRA, NRAHLF.org and for Fox News, Forbes and more for over two decades. His books include “The Ultimate Man’s Survival Guide,” a New York Times’ bestseller, “The Future of the Gun” and “Kill Big Brother.” His latest book is “The Ultimate Man’s Survival Guide to the Workplace.” Miniter is a frequent guest on national radio and cable news shows. His website is FrankMiniter.com.

Follow NRA Hunters' Leadership Forum on Twitter @HuntersLead.

E-mail your comments/questions about this site to:

[email protected]