by Jordan Voigt - Tuesday, March 19, 2019

I consciously tried to calm my racing mind as the elk herd turned and lined out towards the thick timber. The elk knew something wasn’t quite right but couldn’t figure out what it was. I was going to get one brief chance at the only bull in the herd and wanted to make the most of the opportunity. I peered through the lodgepole pines, trying to find a hole to shoot through as the elk started to work higher into the thick timber. I leaned right, leaned left, half the herd was gone now, lost to the cover they were seeking and the bull was almost there. I looked farther down the line and spotted a light break in the trees. If he stopped there, I might have a shot. I shouldered my rifle, flipped off the safety and watched him take the last remaining steps.

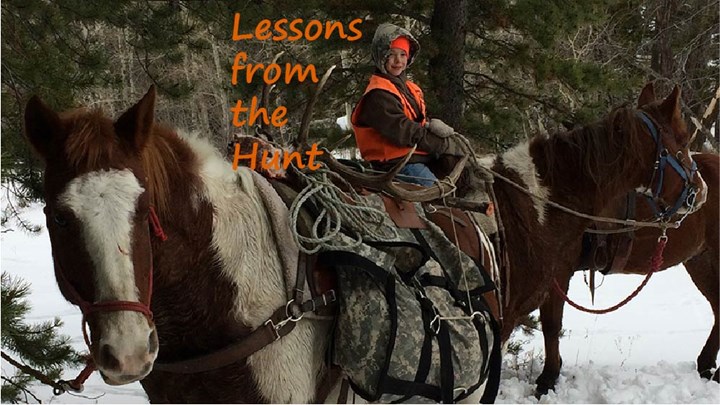

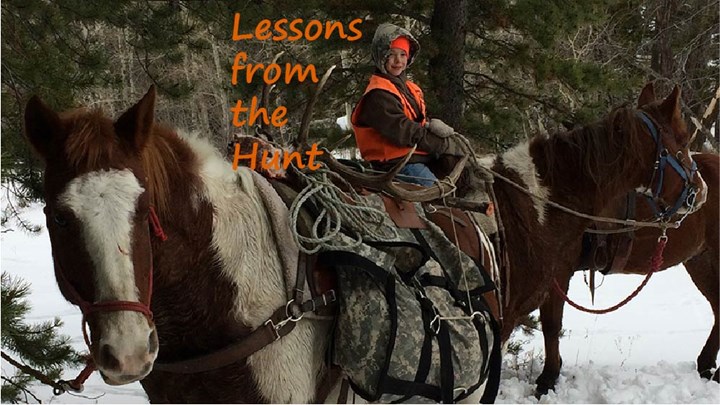

Hunting in my family isn’t a sport, a hobby or even a passion. It’s part of who we are. It’s intertwined in our identity and there’s not a day that goes by that our time in the field together doesn’t affect us. From spring scouting and planning, summer trips to get the stock in shape and the kids some saddle time. Then fall camps and hunts, and finally winter meat processing and starting the process all over again. Together, we relish the cycle of work.

My parents both had horses growing up. Ranching and rodeoing was a tradition on both sides of the family so it was only natural we had them too. As I grew up, my father taught me the importance of respect and care for the stock. Even after a long day, there was no going to the tent until the horses were watered and fed. On cold mornings, headstalls would be brought in and the bits warmed by the woodstove or on the dash of the pickup before saddling.

These teachings were added to with woodsmanship and lessons about the animals: how and where to build a fire, why game animals use the country the way they do, how land features affect wind current, and the list goes on. As a kid I was intrigued to absorb these lessons solely for the sake of becoming a better hunter so I could have the same kind of success as my father. What I didn’t realize at the time was he was imparting much more valuable information than how to boost my success rate. Learning to be responsible for an animal’s care while in the mountains, while at the same time hunting with the ultimate goal of killing another animal is one of the strange juxtapositions we hunters can find ourselves in that nonhunters may never understand. Being exposed to the realities of these truths as a child, I never gave it a second thought as I was taught to take a respectful, responsible role in gathering meat while strengthening bonds with family and friends.

As I’ve matured as a hunter, like most, I’ve started to appreciate the bigger picture of why we do what we do. Memories made have become more important than my tags getting filled. One of my best days in the field was when I didn’t even have a tag in my pocket. A friend had recently gotten home from a tour in Iraq as Marine infantryman. He needed some time in the mountains of our boyhood home so we headed out in the dark one morning. Several hours later, we sat together silently next to his first elk. I snuck a look at him out of the corner of my eye. It was the first time I had seen him smile since he got home.

My father and I still hunt together as much as life circumstances allow although I now have two sons of my own, one of whom will start hunting himself this fall, adding an exciting new dynamic to my and Dad’s hunting season. Sage, now 9 years old, has his own rifle, which he shoots well, and is becoming a pretty good young horseman thanks to his grandpa.

Much to Sage’s dismay, Dad and I took one afternoon to elk hunt—just the two of us. I had a spot to show him where I had seen a herd with six non-legal bulls the week before so we went back to look for their older brother. With plenty of light left, we spotted a herd and, with Dad’s blessing, I took off after them. Several hours of timber hunting later, I had the bull walking toward a small opening. I called to him and he locked up and turned to look back. I checked the sight picture for a clear line to his vitals and touched the trigger. I lost him in the recoil but as the snow drifted down from the percussion through the trees, I saw a patch of dun-colored hide laying behind a log.

After getting the bull opened up for the night and marking his location, I headed for the pickup. Dad was there already, reclining and eating licorice.

“I heard you shoot. Did you get him?” he asked.

Not wanting to waste the moment, I replied, "I missed him,” and let it hang for a beat.

“Not one single time.” Dad grabbed me in a bear hug and we shared a laugh. We made a plan for the next day, Thanksgiving, for him to pick Sage and me up with the horses in tow to go get the bull. We would have all day together and Sage would have a good eight-mile ride to keep honing his horsemanship abilities.

Those of us who enjoy the hunting lifestyle and were blessed with a mentor who gave unselfishly of his or her time afield to start us down the right track have a double helping of responsibility. We must pass on the heritage that was passed on to us, thereby keeping our way of life viable for future generations and also to honor the commitment of others who gave their time so freely to us. It’s easier in the short term to go with a well-known hunting buddy, but there may be someone who needs a day in the field and could benefit greatly from the experience with an avid outdoorsperson.

With society casting an ever-critical eye toward our way of life, it’s vital for each hunter to do his or her part. Invitations to non-hunting friends to come along for a low-pressure hunt can be a good way to pique someone’s interest. Many have just never been given an opportunity and find it overwhelming to try on their own. Another surefire way to get the conversation started is a dinner with your favorite game meat as the main course. I’ve been at several of these events and people who have never eaten wild game are amazed at what can be done with lean, organic meat. Even if people don’t feel comfortable harvesting their own table fare, it demonstrates respect and responsible use of the resource we hold in such high regard. Most importantly, I believe, is to make time to show the younger generation the magic that Mother Nature holds and is willing to share with some effort, patience and willingness to learn.

As three generations of elk hunters drove up the mountain road, I leaned over to Sage.

“Son, grab those headstalls and put them on the dash, you don’t want to put a cold bit in your horse’s mouth.”

About the Author: Jordan Voigt is a lifelong, passionate outdoorsman. He has hunted in several countries and numerous states. He lives in Montana with his wife and two sons and stays busy teaching them about the outdoors. You can follow him on Instagram at @jordan.voigt.

Follow NRA Hunters' Leadership Forum on Twitter @HuntersLead.

E-mail your comments/questions about this site to:

[email protected]