by Brad Fitzpatrick - Monday, November 16, 2020

A white rhino is poached in South Africa’s Kruger National Park by a gang of poachers. A decade ago, there’s little chance these poachers would ever face retribution for their acts. The horn would be ferried off to smugglers who would sell it for a massive profit in Asia. The poachers would earn a quick payday, and the rhino’s carcass would be left to rot under the bright South African sun.

But this is a different time, and game rangers have a new weapon in the war against poachers. Early the next morning, anti-poaching units find the rhino carcass and the tracks of the poachers as they flee toward the park’s boundary. A call goes out and Lucy, a bloodhound, is brought to the scene of the rhino killing. Lucy is a “line dog,” trained to work on a leash and follow scent in the dry, harsh conditions. Bit by bit she unravels the track, and soon Lucy’s handlers believe they are within four hours of the escaping poachers. Another call goes out and the roar of helicopter rotors drowns out the sounds of the bush. When the helicopter lands, a pack of trained scent hounds strikes the track and runs free, coursing through the bush at a pace their human handlers can’t follow from the ground. With the scent of the poachers growing stronger by the minute these hounds pick up the pace, their loud cries indicating they’ve lined out the track and are making good time. The helicopter follows them above, the pilot watching as the hound pack closes the gap on the criminals. The poachers, too, are increasing their pace. But it’s no use. They run as fast as they can, the thorns tearing into their skin, but the pack is at full cry and closing fast. The poachers will never make it to the border of Kruger. When the sound of the helicopter drowns out the dogs, the poachers have already taken refuge in trees, looking down at the pack of hounds that has them pinned. Kruger has lost a rhino, but these poachers will pay.

Before this pack of anti-poaching hounds was deployed in Kruger, the park was losing approximately one rhino every eight hours to poachers. The vastness of the park, which covers 7,500 square miles of African wilderness, makes it a rhino poacher’s paradise; capture rates for poachers were running about 5 percent. In those days there simply wasn’t a good way to catch up to these criminals before they could escape.

The inefficiency of traditional anti-poaching tactics bothered Ivan Carter, a professional hunter and the head of the Ivan Carter Wildlife Conservation Alliance. Around a campfire in Kruger Park, Carter, who has been featured in numerous articles on this website, began discussing the problem with rangers and other stakeholders in Kruger and suggested the best method for capturing poachers might be a quick-reaction team with free-running scent hounds. But where could he find the right hounds, and would they be effective at catching poachers?

Dogged Determination

Carter began searching for a dog handler whose hounds might be capable of pursuing poachers in Kruger. He contacted Joe Braman of Texas Canine Tracking and Recovery and the two began discussing the complex logistics involved with training a group of hounds to chase poachers and then getting those dogs to Africa. Braman felt confident his dogs could capture poachers, and the two men began working with the Southern African Wildlife College (SAWC) to develop a curriculum for dogs and handlers alike.

Early in the development of the course, Braman, Carter and members of the SAWC team were doing a test run with dogs in Kruger. Not every scent hound is capable of tracking poachers, for the terrain and the scenting conditions (which are mostly dry and not conducive to trailing with hounds) were extremely demanding. It just so happened that there was a poaching incident that same day in the park and so the pack’s trial run would be a pursuit of real poachers, an accurate measure of how the dogs could perform. When the poachers’ tracks were located, the dogs were dropped on the trail. They immediately rushed through the bush on the scent, gaining quickly on the poachers who, until that time, had been cavalier about their illegal operations. But when they were faced with a pack of roaring hounds running at full speed behind them, they fled. It was in vain, though, because the dogs captured all of them and they were subsequently arrested. The poachers had a two-hour head start yet the dogs managed to catch them in less than 10 minutes. Carter and Braman knew the plan they had could work, and it seemed they’d finally found an answer to Kruger’s rhino poaching problem.

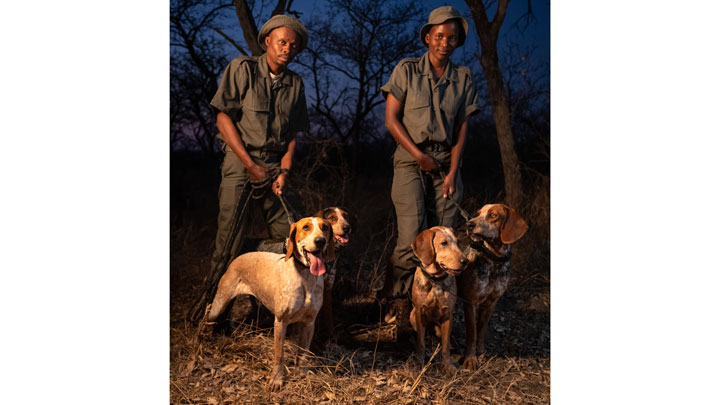

The SAWC team took over the care and training of the hounds, and over the last two years the pack has grown. Initially, 20 dogs were housed at the SAWC facility, but today there are 70 dogs divided into teams of five animals that are ready to deploy at a moment’s notice. Prior to the SAWC hound project, rangers had attempted to use leashed dogs to locate poachers, but success rates were low because dogs wore themselves out quickly by pulling on the lead and human handlers couldn’t keep pace. The SAWC’s pack of free-running dogs is permitted to follow the trail unfettered while rangers watch from the air, increasing the speed of the chase. The system has resulted in a dramatic downturn in poaching: Capture rates with hounds run between 85 and 90 percent, and to date the team has captured over 100 poachers. Today a rhino is poached every three weeks in Kruger, which is far less frequently than before the dog teams arrived.

SAWC now houses the hound packs on its campus near Kruger National Park. The college staff provides for the dogs and helps track down poachers, but they do not make arrests—that responsibility falls to the Kruger Park Rangers.

There’s little doubt the SAWC’s hound packs hold the key to protecting rhino and other wildlife populations in Kruger and across South Africa. The success of the program has sparked interest from other countries in training their own anti-poaching hounds as well, so the program that Ivan Carter and Joe Braman pioneered may be a linchpin in the preservation of wildlife across the African continent.

Importing, caring for and training hounds is not cheap, though. For more information and to lend your support to this program, visit http://www.ivancarterwca.org. By donating, you’re ensuring poachers don’t have the opportunity to wipe out threatened species. Your efforts also will ensure that so long as there are poachers scouring South Africa’s parks for rhinos there will be a pack of hounds at the ready to dog their every step.

About the Author

Brad Fitzpatrick is a full-time freelance writer living in Ohio. His work has appeared in several NRA publications and he has hunted on four continents. Fitzpatrick competed on his university's trap and skeet team and has served as an instructor for 4-H Shooting Sports. He is also passionate about wildlife conservation, particularly when it comes to hunter-funded projects both in the United States and abroad.

E-mail your comments/questions about this site to:

[email protected]