by Serena Juchnowski - Friday, July 17, 2020

Buck fever. Deer shakes. Whatever one decides to call it, all hunters experience some sort of emotional flood with a wild animal in front of them. For me, it usually comes as an intense focus with heightened attention to every movement and sound. Heart pounding and my breath slowing as I line up a shot. Since May 2019, it now comes with more than that.

At the age of 20, during finals week of my second year of college, I was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes (T1D) and was in Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA), a life-threatening complication of high blood sugar. I was terrified, blaming myself. It took a while for me to understand that there is no explanation. I did not do anything to cause it. It does not come from a lifestyle choice, what foods you eat, or how much you exercise. The only treatment is insulin, by either manual injections or through a pump, a device that constantly supplies insulin to the body. The mistake I made, and that many do, was confusing type 1 with type 2 diabetes, which can be caused by lifestyle choices and is associated with excess body weight. Type 2 diabetes can be controlled and only in more advanced stages requires supplementary insulin.

As a competitive rifle shooter, I send thousands of rounds down range a year. I endure heat and match pressure at local and national events while attempting to regulate sugar levels drastically affected by both. Even the shots I took to earn my Distinguished Rifleman Badge in 2019, the highest honor for excellence in civilian marksmanship competition recognized by the U.S. government, did not compare to the shot I took last fall, hunting again for the first time with T1D.

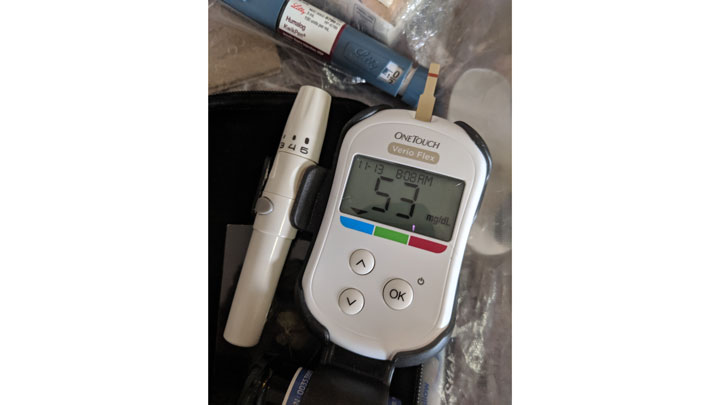

As the NRA has long instructed, when it comes to hunter safety, responsibility and ethics, it is paramount that every hunter take an ethical shot on a wild game animal and be aware of his or her limitations. Type 1 diabetics must constantly balance insulin and carbohydrates to maintain blood sugar control and stay alive. Too much insulin leads to low blood sugar. I start shaking, my brain stops working and I can slip into a coma. It is immediately dangerous. High blood sugar is less dangerous in the short term, but it can cause blindness over time.

For the majority of last year, I used old-fashioned testing strips and insulin pen needles. Insulin in vial form must be refrigerated, insulin pens do not. Shooting in the hot sun not only causes low blood sugar, but also inactivates insulin and test strips. I quickly discovered that I needed to wrap my insulin in some sort of fabric and pack it away from the ice packs in my cooler to keep it functional but not frozen. While I still have not found the perfect solution for colder Ohio hunting seasons, I keep my insulin pens in a pocket close to my body or in the vicinity of a hand or body warmer. This is also a balancing act as it is also not good for the insulin to be too close to a heat source, even an artificial one.

Many diabetics use insulin pumps, which attach to the body and inject insulin in smaller doses more frequently. The user still must specify dosages. I made the decision to utilize insulin pen injections because the primary location for a pump is on one’s stomach and I did not want to have something in the way while shooting prone. To give an injection while hunting, I have to find a way to keep my insulin from freezing and to find a spot to inject in my stomach under layers of clothes. The greatest challenge is staying quiet while doing this, opening snacks and monitoring blood sugar.

A continuous glucose monitor (CGM) changed my life and allowed me to more easily and responsibly function in the world. I use a Dexcom, a small, low-profile device that attaches to my stomach but does not disrupt prone shooting. It reads my blood sugar every five minutes and sends the readings to my phone. I can see if I am trending up or down before it gets dangerous. Though I must be sure to turn off the high and low alarms before heading out into the woods, it still gives me a way to monitor my levels in the field.

Stable blood sugar is crucial to taking a safe and ethical shot on a game animal. The reason I say that the shots I take while hunting are harder than those in a match setting is that there is more at stake. Though firearm safety is paramount in both areas, hunting involves harvesting a living creature. Any shot placed on a game animal, whether with a bow or firearm, must be clean, accurate and ensure a humane death. Low blood sugar levels greatly impair a person’s ability to take an accurate and humane shot. This does not mean that diabetics should not hunt. It means that diabetics should take extra time and care in their hunt preparations. Diabetics should have food or sugary drinks on hand—twice the amount you believe you will consume. T1D is unpredictable. There is no way to predict exactly how my body will react on any given day and it is better to be over prepared.

Over one million Americans live with T1D. However, most type 1 diabetics are diagnosed at an early age during childhood. It is a part of daily life that always has been there. As someone who was diagnosed at age 20, I knew and knew well what life was like before. Now I choose to save my own life every day and am constantly learning. Everyone’s body is different—and no one has the same experiences. The fear and frustration I initially experienced fueled my desire to not let T1D dictate how to live my life. A little over six months after my diagnosis, I harvested a beautiful 9-point buck with a crossbow. I kept my sugar slightly elevated and before taking the shot took a bite from a granola bar. As I expected, my CGM revealed that my sugar dropped quickly and drastically from the time I saw the deer until the time I made the conscious decision to harvest it.

I hope that I can help inspire others with disabilities, especially those diagnosed with T1D at an older age, to follow their dreams and to do what works for them. Do not be afraid to either return to hunting or to try it for the first time. Learn from my experience and understand that hunting with T1D just takes more preparation and responsibility.

Fortunately, there are many resources available to those who suffer from diabetes, such as materials provided by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes education and support goes far in empowering those of us with the disease to navigate self-management decisions and activities.

E-mail your comments/questions about this site to:

EmediaHunter@nrahq.org