by Jim Heffelfinger - Tuesday, May 31, 2022

The passage of the $70 million Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) Research and Management Act (H.R. 5608) last December was applauded by agencies and conservation organizations as an important step in combating CWD. Passage by the Senate is all that is required to provide critical resources for researchers and managers to make gains in our understanding of the disease and management options. H.R. 5608 passed with a resounding 393-33 bipartisan vote and was sent to the Senate. On April 28, the Senate version—S. 4111—was introduced and quickly referred to the Senate Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry Subcommittee.

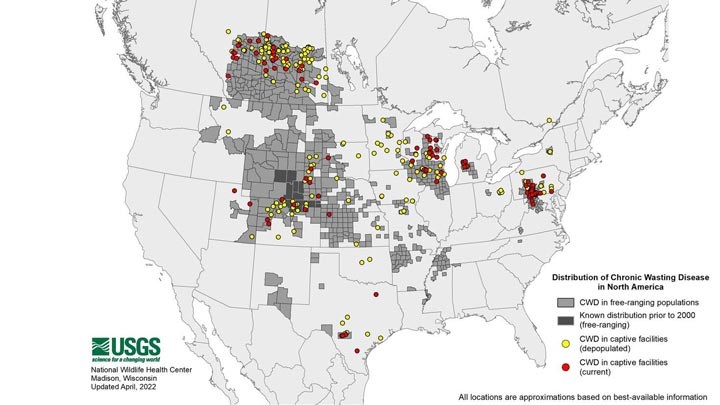

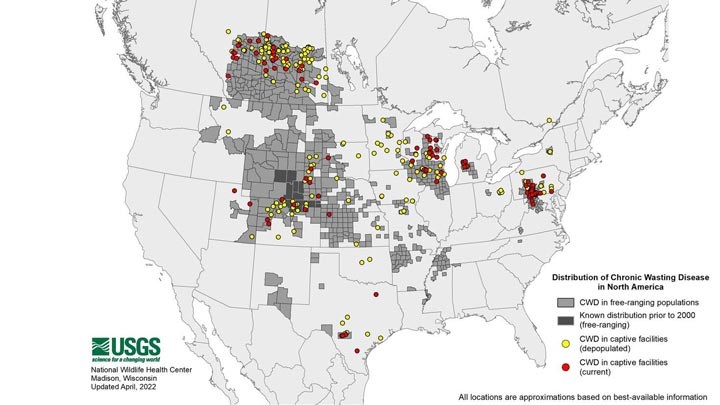

This bill is vital because CWD is a significant concern for our native members of the deer family and addressing it will require significant resources. CWD was first discovered in 1967 in a wildlife research facility in Fort Collins, Colo., but not detected outside Wyoming and Colorado until 1996. Despite growing efforts to test for it in other states and provinces, it did not appear to spread geographically for a few decades. Eventually, it started to pop up in new states and provinces at a slow burn. As is typical in disease ecology, the rate of spread has accelerated in recent years with five new states and provinces joining the “CWD Club” in the last eight months. Since October 2021, CWD has been discovered in Manitoba (October), Idaho (November), Alabama (January), Louisiana (February) and North Carolina (March). Most states that have not detected the disease already have CWD Management Plans on the shelf and ready for what seems like the inevitable. To date, CWD has been found in wild or captive members of the deer family in 30 states, five Canadian Provinces, Finland, Norway, Sweden and South Korea. This disease is 100 percent fatal, has no cure and does not respond to vaccines or antibiotics. The infectious agent (prions) can be spread through animal-to-animal contact, saliva, feces, urine, discarded carcasses and soil contaminated by any of the above.

It is not only the geographic spread that is concerning, but also the continual increase in the percent of the populations that are CWD-positive (prevalence rate). We now have enough data to model the effects of this disease on deer population performance. It appears that when more than 27 percent of the population is positive for CWD, it will affect the abundance of deer. Currently there are a few game management units in the West where more than 40 percent of the deer are infected. For hunters in those areas, that’s nearly a coin flip’s chance you are driving home with an infected animal in your truck. Deer live about two years after becoming infected. Since prevalence is higher in bucks, and even higher in mature bucks, we shouldn’t expect a mature-male age structure in populations that have had unmanaged CWD for a long time.

Understanding what we know thus far about CWD emphasizes how much we need to know more. Senate Bill 4111 is the way forward to address this insidious deer killer. The very first words in the Senate bill concisely frame the need: “Chronic wasting disease, the fatal neurological disease found in cervids, is a fundamental threat to the health and vibrancy of deer, elk and moose populations, and the increased occurrence of chronic wasting disease in regionally diverse locations necessitates an escalation in research, surveillance, monitoring and management activities focused on containing and managing chronic wasting disease.” Putting money where their mouth is, the bill allocates $35 million for research and $35 million for management of CWD annually for a total of $70 million for fiscal years 2022 through 2028.

The bill directs the U.S. Department of Agriculture to enter into agreements with state and tribal wildlife and agricultural agencies (75 percent of the money) and university and research facilities (25 percent). Research will focus on transmission pathways, improved detection (especially on live animals), long-term suppression or eradication and genetic resistance. Eradication is not likely with the tools available today, but that’s what research is for: to uncover solutions to problems we currently think are impossible to solve. This research then informs the implementation of management strategies to combat CWD on the ground.

Management efforts will be funded if they can potentially reduce transmission, increase resistance and slow or stop the spread and prevalence of the disease. Funds will help agencies develop materials to inform and educate the public about the disease. This bill would allow agencies dealing with the ecological and fiscal fallout from CWD to be proactive—not just reactive—in addressing this threat to the deer family. We need more research and we need to learn more about effective disease management strategies. In looking at the increasing progression of this disease, we must stop observing and documenting and start trying to manage CWD on a landscape scale.

State, tribal and provincial agencies are on the front lines of this issue—they are quite literally the tip of the spear. When a new jurisdiction discovers CWD, it is forced to suddenly divert hundreds of thousands (or even millions) of dollars from wildlife conservation to learn about and manage the disease in its state. Since so much of the on-the-ground burden is on wildlife agencies, it makes sense that this bill leans the funding their way. The structure of this bill follows a successful model that was used to conserve wildlife seasonal habitat and migration corridors where the initiative is coordinated by federal agencies, primarily implemented by the states, and guided by needs they identify. The bill also calls for the review of the existing captive CWD herd certification program to find ways to minimize or eliminate interaction between wild and captive deer species, increase participation in the program and find more-effective methods of detection of CWD-positive animals.

Funds will be prioritized to states, tribes and research facilities that have the highest prevalence of the disease in their herds and those that have comprehensive programs and polices focused on addressing this threat. There is a provision to make funds available on short notice if a jurisdiction discovers CWD for the first time. In the early stages of detection, it is important to quickly learn the geographic extent and prevalence of the disease because management efforts early on have the most chance of stopping the spread or at least managing the CWD at a lower level. Research by Colorado Parks and Wildlife indicated the disease was much easier to control if management strategies begin while prevalence rates are still below 5 percent of the population.

The mounting evidence indicates CWD is not going to disappear due to neglect—on the contrary. This bill gets resources in the right hands to learn more, and do more, to address this growing threat to wild and captive deer herds.

About the Author

A wildlife biologist with degrees from the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point and Texas A&M University-Kingsville, Jim Heffelfinger has worked for state and federal wildlife agencies and universities and in the private sector. He is the author of Deer of the Southwest and the author or coauthor of more than 200 magazine articles, 50 scientific papers, 20 book chapters and numerous outdoor TV scripts. Chairman of the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies’ Mule Deer Working Group representing 24 Western states and Canadian provinces, he also is the recipient of the Wallmo Award, presented to the leading mule deer biologist in North America, and was named the Mule Deer Foundation’s 2009 Professional of the Year. A member of the International Defensive Pistol Association and the U.S. Practical Shooting Association, Heffelfinger enjoys weekly competitions with his 1911. The opinions expressed here are his own and reflect his personal point of view.

E-mail your comments/questions about this site to:

[email protected]