by Cody McLaughlin - Thursday, July 21, 2022

Above: Daryl Lescanec of Alaska’s Department of Fish and Game hopes more people will take up bowfishing to help the state control invasive fish populations.

Sportsmen are, above all, conservationists. From the funding we generate for conservation through license fees to the donations we generate for the same to the role we play in the management of key game species such as whitetail deer and black bears, we do a lot for the great outdoors. Bowfishing is one of these management tools. Used to target unwanted “rough” fish such as booming populations of invasive species, it provides a high rate of success and liberal bag limits that help you to keep your archery skills sharp.

I recently caught up with biologist Daryl Lescanec of Alaska’s Department of Fish and Game (ADFG) about this important sport, it’s uses as a management tool and his hopes for its future in the Last Frontier State. We spent a couple days traversing 158.8 miles of Alaska’s Susitna River Drainage, camping at an old ADFG cabin, and learning about northern pike as invaders and how bowfishing is a tool the state hopes to make better use of in years to come to manage them.

“So,” I asked Lescanec, “Is this helping make a dent in invasive fish populations? Bowfishing?”

“No,” he replied “But that’s because not enough people are doing it. I’d like to see tournaments and stuff like they do down in the Lower 48.”

Bulchitna Lake, about a mile behind the cabin where we stayed, was ground zero for the northern pike’s introduction in the southern part of the state. In the 1960s, someone illegally introduced them to the lake, from which they have spread throughout the entire Matanuska Susitna Valley. Pike is a species native to waters north of the Alaska Range, the large mountain range that bisects the state horizontally.

I asked Lescanec to put me in touch with Parker Bradley, the ADFG’s regional pike biologist, to talk about the data behind ongoing attempts to remove invasive pike. While Alaska has done great work eliminating entire populations from local lakes, it comes at a cost. The chemical treatment that it uses, known as rotenone, kills all fish in the lake, necessitating the restocking of native fish populations.

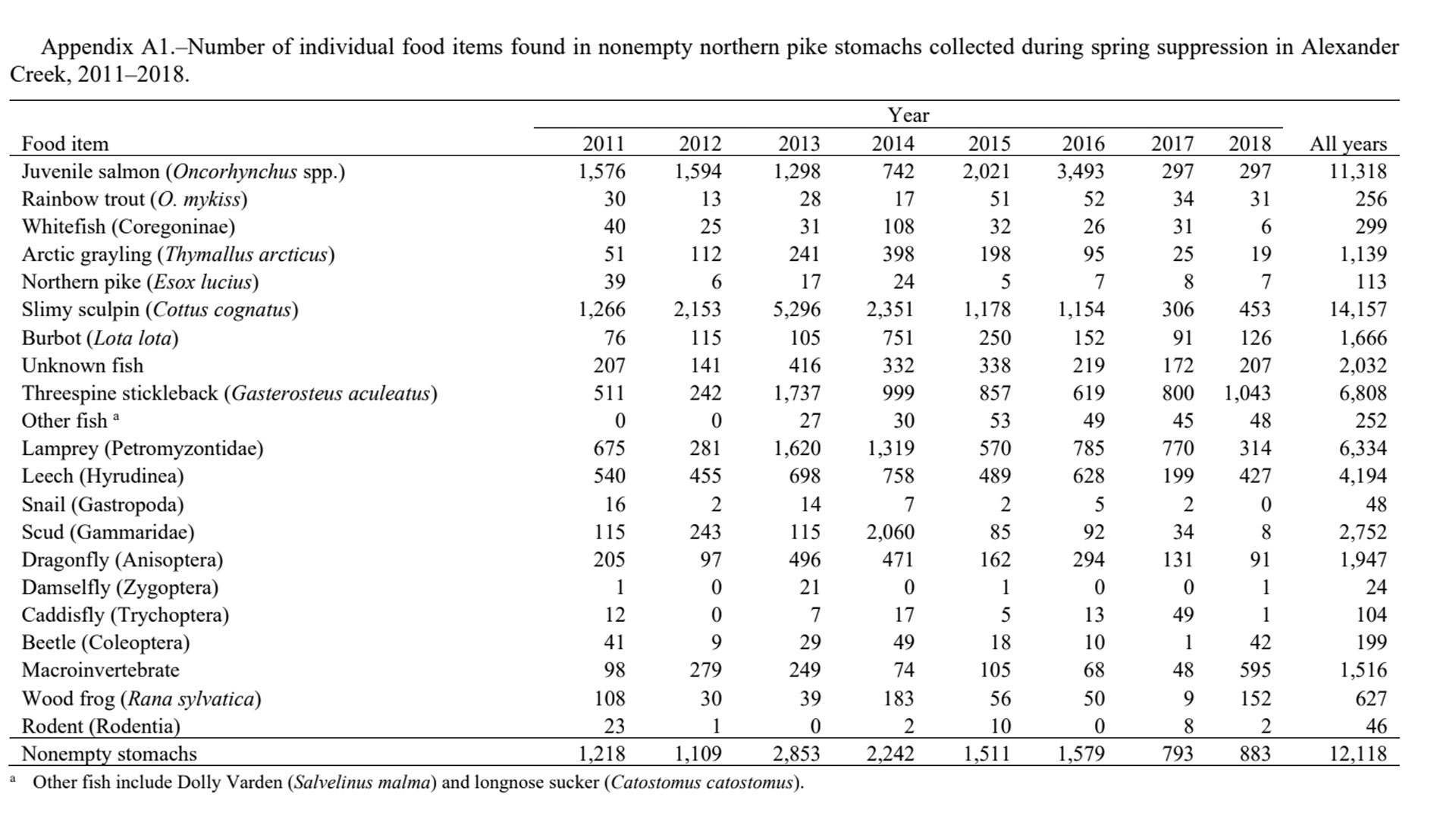

According to Bradley, Appendix A1 from the September 2020 report, “Fishery Data Series 20-17: Alexander Creek Pike Suppression,” documents the prey items for pike in Alexander Creek from 2011-2018. “One interesting thing, and this is very common throughout the valley,” said Bradley, “is that despite pike being the most common species in some of these systems, they are one of the least common prey items by other pike (i.e., cannibalism rates are extremely low). Even in systems where there are no other prey fish available [because pike already ate them all], their diets are dominated (97-98 percent) by invertebrates.

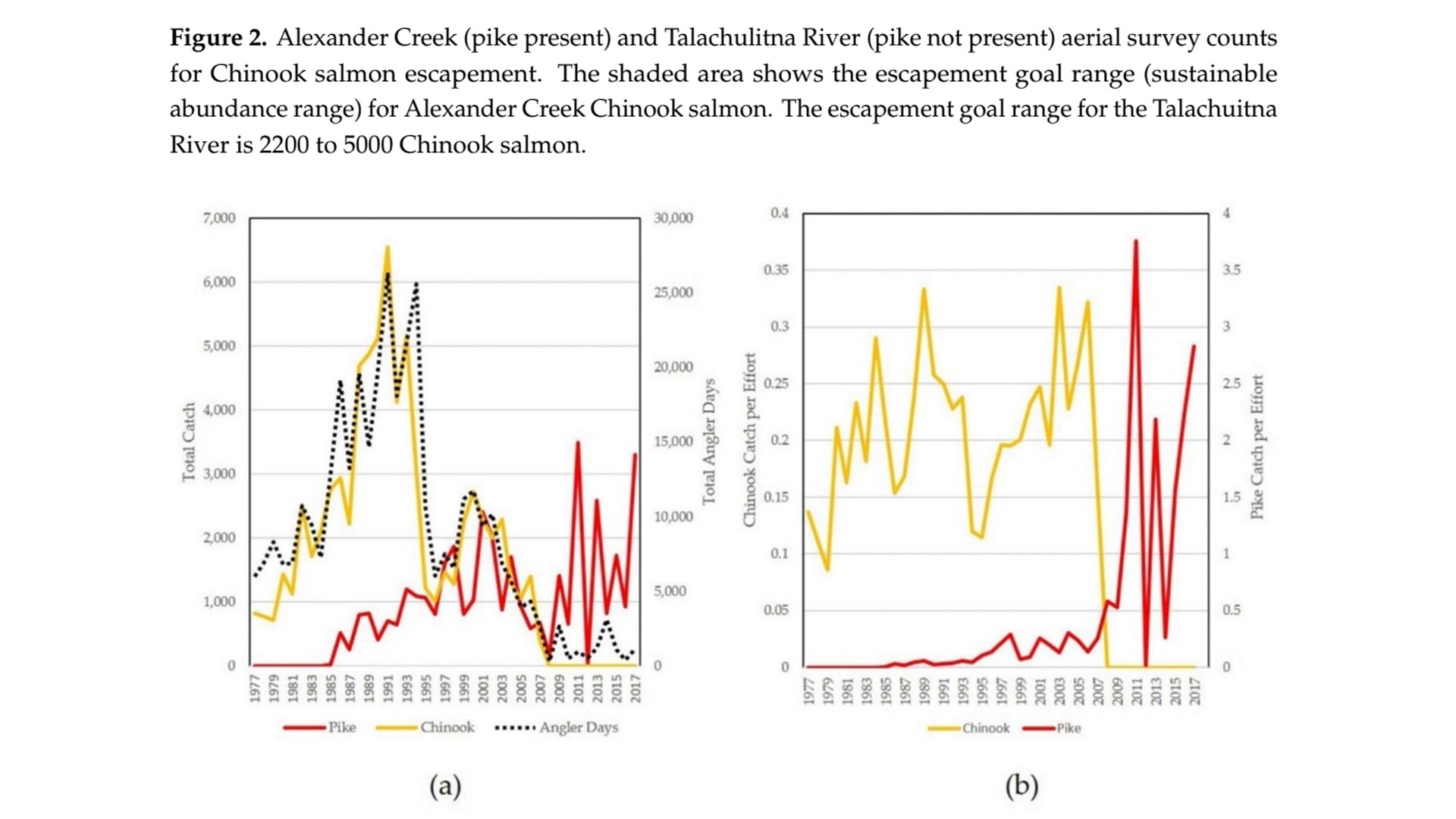

Similarly, in a 2020 paper by Kristine Dunker, “Native vs. Invasive Pike, A Tale of Two Ranges,” Figure 2 (shown below) is interesting as it shows two systems with similar escapement goals for chinook salmon, also called king salmon due to being the largest salmon sub-species: Alexander Creek, where pike are present, and the Talachulitna River, where pike are not present. The effects of pike predation on juvenile king salmon can really be seen beginning in the early 2000s. Where the adult king aerial survey counts, for example, were almost identical through the 1980s and 1990s, Alexander has been averaging about 40 percent or less of what it should be since then.

As far back as 2013, the article “Invasive Pike Thriving on Salmon, Other Species” in the Alaska Journal of Commerce tracked federal and ADFG studies on the impact of non-native northern pike on salmon populations. It noted that in areas where their habitats overlap, salmon recovery may depend on suppressing pike. In the federal study, which included examining 274 pike, researchers found more than 600 salmon in the stomachs of the pike, with several of the predators having eaten more than 20 juvenile salmon each.

“As some of this relates to bowfishing,” said Parker, “any increased harvest is beneficial. The nice thing about bowfishing is you can be very successful regardless of whether the bite is on.” And while some of those big females can be hard to entice with lures, he notes that they effectively can be targeted with bowfishing equipment, particularly in the early spring when they’re in the shallows.

“It doesn’t matter if they’re in the feeding mood or not,” Parker explains. “I’m sure you heard about the new pike bowfishing world record someone got in Big Lake this spring,” referring to the photo below of young Lexi Dockstader and her 28.6-lb. pike that measured 48.5 inches. “This pike was a female, and a fish this size can produce a few hundred thousand eggs each year,” he added, “which greatly adds to the future pike population.”

When it comes to bowfishing in Alaska, there is ample opportunity on rivers like the Yentna and Deshka and their feeder creeks along with lakes such as Big Lake where Dockstader captured the world record in May. Pike also are a challenge for Lower-48 bowfishing hacks like me, who are used to shooting at rotund carp and catfish. Compared to many other fish species, pike have a much thinner profile and require a degree more of skill to hit consistently. Missing by literally an inch is more common than you think. Despite being dialed in, I still wish my shot at that one skinny 12-incher had been successful.

While this challenge-added aspect makes it all the more fun, it’s also a great way for archery hunters to hone their skills in a high-action sport during the summer months when daylight runs long. It’s not unusual to shoot a hundred arrows in a day when bowfishing, which pound for pound gives you more opportunity than even small game hunting and, in my view, is more fun than just flinging arrows down the range.

Getting Started in Bowfishing

There’s no doubt that having a boat will increase your success when bowfishing, but you don’t want just any old boat. The classic configuration is a flat bottom boat. Bass Trackers are popular, with high powered LED light bars around the boat’s bow that are aimed at the water. There is normally a deck on the bow that lifts shooters anywhere from 6 to 18 inches off the bow to provide for better visibility and aiming. Trolling motors are a popular option, especially for solo practitioners, but if you’re willing to put in the work, a push pole will do just fine. Bank fishermen have it a little bit cheaper. Just grabbing the highest-lumen head lamp you can get will work, and for daytime fishing, polarized sunglasses are a huge help.

Setting up your bow for success requires a different kind of practice and dialing in compared to longer-range bowhunting. You’re making shots within a short distance and need to trust your aim is true while using an arrow without fletchings. Lescanec’s system, among the better I’ve seen, meant taking along a shooting back for Creekside dial-ins whenever necessary and a “practice arrow”—an old fiberglass bowfishing arrow without line attached to practice a shot or two to ensure the bow was still dialed in after the 50th—or hundredth—shot of the day.

More importantly, my advice is to set your bow poundage low for a couple reasons. First, it still will penetrate. Getting stuck in the mud or “the cabbage” will waste time and valuable shot opportunities. And remember that you’re flinging arrows in a numbers game. It’s not uncommon to shoot a couple hundred shots in one outing. You don’t need 60-plus pounds to hit a pike or even a carp or flathead catfish in the Lower 48.

As for the challenges you’ll face, “If a guy needs a challenge, Arctic alligators man,” says Lescanec. “These pike are hard to hit.” Aside from the particular challenges of the quarry that I mentioned, there are the universal challenges when it comes to fishing with a bow and arrow.

The most obvious difference between target shooting and bowfishing is that fish are moving targets and when spooked they can be hard to hit. A slow and steady approach using a push pole or trolling motor is a solid play to get within that magic 10 feet or so before you pop off a shot.

Light refraction is the No. 1 problem as it is 10 times tougher than you think to hit a fish that is under even the clearest, cleanest water. Learning to correct in real time for not only movement and depth but also when it comes to how the light refracts off the surface takes much more skill than shooting at a bag target, even at long distance, and just takes time and experience to master.

I had my own issues just spotting the pike while fishing with Lescanec. In one memorable exchange, he said, “There’s one!”

“Where?” I asked, one hand over top of my polarized shades.

“In ’em.”

That was the only shot he made that day. As I watched him pull in the fish, it was clear I was bowfishing with a pro.

As for visibility, it can be broken down into two scenarios: day fishing and night fishing. During the day, a good pair of polarized sunglasses is worth its weight in gold. I feel that green coloration is best for maximum visibility into water. Nighttime is a different story as most boats rig up high-wattage light bars to see into the water in the dark, and bank fishermen can produce a similar effect with a high-quality head lamp.

Speaking of visibility, wind (and the waves it generates) creates a ripple effect on the water which greatly reduces it. Even if you do manage to spot fish, it makes your internal calculations on aim and adjustment for light refraction that much more difficult as it is almost impossible to judge depth and distance. The commonly accepted wisdom is that winds over 10 mph are a no-go on shooting fish so find sheltered water or wait out the wind.

Bowfishing is a win-win for hunters, archers especially, looking for a hobby to hone skills and keep them sharp during the off season in between scouting trips or planning sessions. What’s more, it directly contributes to the conservation of other fish species by removing detrimental invasives from the ecosystem before they can cause more harm. Sportsmen in Alaska and other states should consider giving it a shot.

E-mail your comments/questions about this site to:

EmediaHunter@nrahq.org