by Mike Arnold - Thursday, November 9, 2023

Editor’s Note: The timing of this article is fitting as the NRA celebrates America’s first-ever National Wild Game Meat Donation Month, touting hunters’ role in fighting food insecurity by donating their wild game meat to help feed those less fortunate. This article underscores the vital role hunters play in local communities not just in America but worldwide.—KMP

When people think of food in a first-world country, we think of variety, whether as hors d'oeuvres, a main course or dessert. The fact that we even consider “courses” normal reflects our bias toward expecting the bounty always available. When locals in poor, developing countries think of food, they expect regular hunger, and even starvation. That is why a recent conversation at an African hunting lodge I participated in made such an impression. At first, what the other speaker said struck me as incredibly uninformed and even hard-hearted. Then I realized he was simply voicing what I often thought myself, particularly about the types of meat protein I prefer.

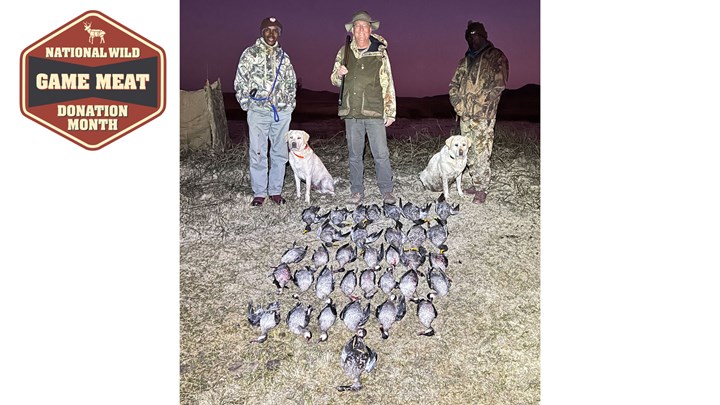

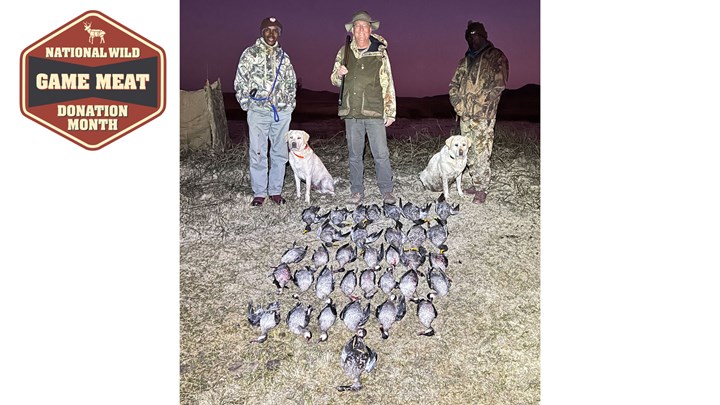

The conversation began as I related the wonderful hunt provided by the folks at Stormberg Elangeni Safaris. When planning my safari at their property in the Eastern Cape of South Africa, I mentioned wanting a “bird hunt” for a magazine article. They came through in spectacular fashion with pursuits of guinea fowl, grey-wing partridge and the focus of the conversation: a late-afternoon duck hunt netting 35 ducks of various species. The other hunter quipped, “Why would you shoot ducks when no one likes eating them?” Like I said, my annoyance started raising its ugly head until I realized that I wasn’t a big fan of duck meat either.

Gathering my thoughts, I explained to my listener, and the larger group that now circled me, that we were thinking about it like first-worlders—in other words, like those who always had choices in what they prepared for meals. I then went on to relate how delighted our trackers and dog handlers, Vusi and Mfundo, were when faced with the prospect of being able to distribute the duck-hunting largesse among their friends and families. “In fact,” I explained, “I felt bad that I was keeping one of the ducks for mounting instead of letting them have it for food.”

Some of the listeners, including the original skeptic, continued a bit of nose-wrinkling about the provision of ducks as a meat source, so I pointed to one of the indicators of want with which we first-worlders are familiar. “Have you seen the swollen bellies of small children in the videos and photographs used in appeals for money for those suffering through famines?” I asked. Most nodded. “That is kwashiorkor. It’s a sign of protein deficiency, and once the children show the swollen belly, they have cognitive disabilities, increased susceptibility to diseases and reduced life expectancy. All because they had limited access to protein.”

I continued to push. “Look around at the children playing on this property. Do you see any swollen bellies? The answer will be no. It’s the same wherever sport hunting exists with an outfitter and staff committed to distribution of meat protein harvested by visiting hunters. The ducks I shot may seem like a poor meat to those of us who can choose chicken breasts, ribeye steaks or hamburgers from our local supermarket, but those 35 ducks represent the difference between healthy and sick kids, and empty or full stomachs of members of entire families. It’s that simple, and that significant, in terms of what hunters provide through hunting and daily fees, and the animals taken.”

I’ve witnessed the same positive effects on the welfare of impoverished, local communities from hunters’ participation in the sport we love whether in Africa, Mexico or Central Asia. An early, and major, benefit is the provision of protein—always the limiting factor in nutrition in developing countries. It was the same with my own ancestors who landed on the eastern shores of North America.

My European forebears sought continually through forests and plains for animals that could satisfy their bodies’ essential need for protein. Their needs, and the market hunting built up around the demands for meat by urban communities, led to diminished populations of most meat-bearing species east of the Mississippi, including whitetail deer, turkeys, bison, elk, ducks, etc. Only through the intervention of sport hunters in the early part of the 20th century did the tide turn in North America with the reintroduction and conservation of ecosystems and wildlife. But that’s a story for another time. Now that our group seemed primed to hear about the positive influence on the locals’ lives, I brought up what I considered an even more interesting story about an animal considered a delicacy by the Xhosa tribespeople.

I need to set the stage a bit for this chapter in my discussion of hunter-provided meat protein. As an undergraduate and graduate student, I trained and worked as a mammologist for six years. One of the animals I came to know through scientific literature and nature shows was the rock hyrax, known by Africans as the dassie. Looking a lot like a North American marmot, as their name implies, they hang out around rock outcrops, sometimes in colonies with burrows like West Texas prairie dogs. Dassies are well-adapted to their subterranean habit and tough, foliage-based diets, with powerful forearms, long claws on their front feet and large incisors for cutting grasses and roots for food. But—and this applies to me—they don’t leap immediately to mind as a source of choice meat.

When I encountered rock hyrax on my very first safari years ago, I told my professional hunter (PH), Arnold Claassen, that, if possible, I wanted to collect one. He looked at me like I was crazy when I mentioned wanting one for my game room. I tried to explain all my work in museums curating thousands of small mammals—bats, rats and even marmots and prairie dogs—but he still thought I was nuts. I never did have an opportunity of taking a dassie on that first trip, nor on my other African trips. When I reached the Stormberg property on this particular trip and saw the wealth of rock hyrax burrows and the large number of the little guys running across the landscape, I told my PH, Dave Birch, I wanted one.

Initially, Dave too thought I was kidding. Stormberg’s tens of thousands of acres of free-range habitats host a wealth of game animals, mammals and birds, but dassies are definitely not on their typical list of hunting options. Dave was a great PH who understood “the customer is always right.” I assumed that trackers Vusi and Mfundo also would be rolling their eyes when they heard I wanted one. I could not have been more wrong. Not only were they delighted in me collecting one, but they were also hoping I would shoot many of the little overpopulated animals. I asked Dave why the trackers seemed so happy about my crazy desire. He laughed and said, “The Xhosa love the Dassie meat, stir frying it with curry spices. Obviously, very few of our clients want one, so they look on you as a godsend.”

So, Dave, Mfundo, Vusi, my wife, Frances, and I spent hours spot-and-stalking burrows and rock outcroppings, me armed with Dave’s .22 Hornet and a 4 Stable Sticks Ultimate Carbon shooting rest. You might think this would be an easy hunt. It wasn’t. Getting within .22 Hornet range and hitting the 2-inch-square head on these wary little mammals was difficult, and a ton of fun. Like prairie dogs and marmots, they must keep constant watch for a host of predators, from hawks and falcons to caracals, jackals and snakes. They would let us get within 100 yards and then their alarm signal would go up and they’d all disappear. It was particularly difficult to approach the older and larger individuals.

So it was that my first dassie was medium-sized, and not what I wanted for mounting. However, the care shown by Mfundo in skinning this animal was as great as for any of the other animals I’d taken. This was to protect every scrap of meat that would serve as the main course for dinner. I was successful in bagging one of the big males, so two rock hyrax found their way onto a Xhosa family’s dinner table. That knowledge gave me incredible joy. I love when hunters provide food for others. That’s why, for me, America’s own “Hunters for the Hungry” programs that groups such as the NRA support are so important in helping those less fortunate. This is why the NRA proclaimed November National Wild Game Meat Donation Month. We hunters know that every time we donate a whitetail deer or other game meat in America that many people are fed. It doesn’t get much better than that.

When I described the trackers’ plans for the dassie fry-up, the group surrounding me near the Stormberg lodge’s bar, after-dinner drinks in hand, groaned. I smiled and said, “Remember, we have an abundance of food unheard of in this or any other developing country. I would also like to suggest that we have lost our sense of adventure when it comes to food. The dassie probably tastes fantastic, but we won’t know if we don’t try it sometime. I would also claim something else that is more uncomfortable for me to face as someone from a wealthy, developed country where a profusion of everything is my expectation. I think it’s safe to say that many of my countrymen and women, like me, have lost any sense of thanksgiving for food provided.” I ended my preaching with that comment and shook hands and agreed to disagree with those who remained unconvinced.

In Africa, and elsewhere, I’ve watched the incredible gratefulness of the locals for meat supplied by hunters. International sport hunters should be proud of their impact and legacy in this regard. We also should call ourselves to account if we realize our own lack of appreciation when it comes to the food security that we experience every day of our lives.

About the Author

Mike Arnold is a professor of genetics at the University of Georgia and author of the 2022 book Bringing Back the Lions: International Hunters, Local Tribespeople and the Miraculous Rescue of a Doomed Ecosystem in Mozambique. Mike’s book is available for purchase by clicking here.

E-mail your comments/questions about this site to:

[email protected]

Proudly supported by The NRA Foundation and Friends of NRA fundraising.