by Karen Mehall Phillips - Friday, January 19, 2024

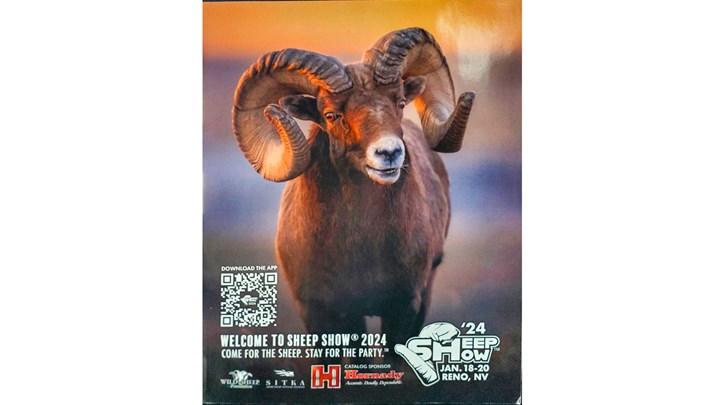

“Come for the sheep, stay for the party” is the fun catch phrase the Wild Sheep Foundation (WSF) uses to promote its annual convention, a gathering of 15,000-plus WSF members and other hunter-conservationists to celebrate what is popularly known as the “Sheep Show.” But for us Sheep Show attendees here in Reno, Jan. 18-20, the words mean much more. We are here because we are hunters who care about sheep, celebrate their value as a precious wildlife resource, and want to support the WSF in sustaining their populations into the future—regardless of whether we ever get to hunt them, considering the cost of such hunts exceeds many hunters’ budgets. This is because the opportunity to hunt wild sheep is likely the most tightly controlled of all big-game species—and rightfully so—as wild sheep exist in limited numbers.

What is remarkable is the extent to which Sheep Show attendees interact like members of a tight-knit family on the show floor and at the WSF’s evening banquets and other special events. This is what happens when you draw hunters united over a common cause—conservationists who understand we are a part of, not apart from, nature, who yearn to maybe one day hunt a sheep of our own or to just climb the mountain to try and get a glimpse of this precious wildlife resource that is here because of the WSF and hunters’ dollars.

When it comes to the critical role of the WSF, most hunters are aware of how we’ve brought back species such as the whitetail deer and wild turkey from the brink of extinction, but wild sheep are on that list too. By the 1960s, bighorn sheep populations—one of North America’s four sheep species along with the desert bighorn, Dall sheep and stone sheep—had dropped to historic lows. In 1974, a group of hunters who were concerned about the future of the continent’s wild sheep established the Foundation for North American Wild Sheep (FNAWS). FNAWS was incorporated as a nonprofit in 1977 to begin raising funds to restore wild sheep and protect their habitats. In 2008, FNAWS changed its name to the WSF to reflect its expanded vision of “ensuring that wild mountain ungulates and their habitats worldwide are managed, utilized, accessible and supported.”

Nearly 50 years later, the WSF has raised an impressive $136 million as noted in its Fiscal Year 2021-2022 Annual Report (July 1, 2021-June 30, 2022), the most recent report available on the WSF website (so today’s dollar figure is even higher). The scope of projects it funds includes: wild sheep transplants, research, water development, predator management, educational outreach and other WSF initiatives. As a result, the numbers of Rocky Mountain, California and desert bighorn sheep have soared threefold continentwide—from about 25,000 in the 1950s to 85,000 today. Some states report 200 percent increases in their wild sheep populations, while the state of Oregon says its wild sheep numbers have risen a stunning 2,000 percent. This is thanks to the thousands of WSF, Chapter and Affiliate members who also are working to fight respiratory disease afflicting wild sheep, to conduct new studies and revise management plans for Dall’s and Stone’s sheep, and to advocate for the long-term health and sustainability of wild sheep herds and their habitats worldwide.

A lot of hard work happens, thanks to this relatively small and tight-knit circle of hunters who gather at this annual convention. For example, that same annual report also notes that the WSF raised and handed over$6,642,784 in 2021-2022 alone, set aside as follows:

Such success takes strategy and commitment. So, the WSF’s modern-day vision is to support wild sheep conservation and management in North America and in Central Asia through focusing on five primary goals:

Advancing the WSF cause are American hunters who recognize that growing wild sheep populations and the resulting increase in hunting opportunities takes reliable funding from generous donors, hunters and nonhunters alike. In early 2024, the WSF launched its Take One, Put One Back (TOPOB) program so those who have gotten to hunt sheep (or who are simply passionate about securing their future) can “pay their good fortune forward” through donor-directed, project-specific funding to “put more wild sheep on the mountain.”

The wild sheep resource is limited and sheep are expensive to hunt, but for me, that’s okay. Maybe one day ... . In the meantime, I’m a proud member of the WSF’s “Less Than One” Club. That’s a fun way for us sheep enthusiasts who have never taken a sheep to say we don’t have even one wild sheep species, but we still dream about it. The essence of the hunt is the anticipation—and we have that in droves.

WSF President and CEO Gray Thornton and Director of Marketing and Communications Keith Balfourd do a great job of promoting the WSF mission of enhancing wild sheep populations, promoting scientific wildlife management and educating the public on sustainable use and hunting’s conservation benefits while promoting hunters’ interests. While the WSF’s success to date might seem like “mission accomplished,” they are quick to share how the work must continue 24/7 if sheep are to exist for future generations to enjoy them. Fortunately, despite the 21st century challenges to wildlife and wild places, the WSF is fulfilling its purpose: “To Put and Keep Wild Sheep on the Mountain.”

This is what it works at every single day.

E-mail your comments/questions about this site to:

[email protected]