by Erin C. Healy - Thursday, January 9, 2025

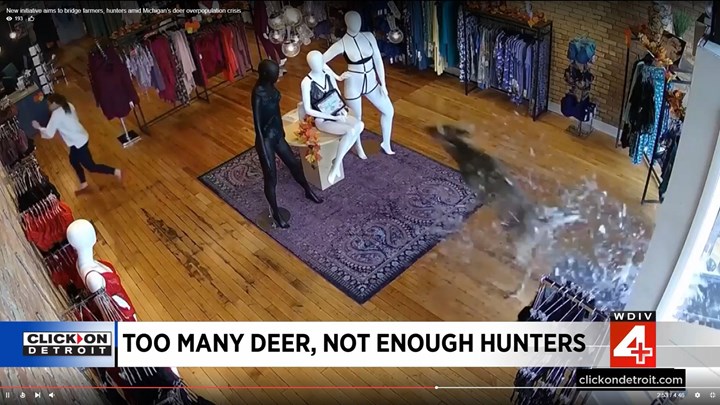

Above: As shared in a Click on Detroit video on Dec. 23, 2024, a new deer management initiative aims to recruit more hunters to help control exploding deer populations in Michigan.

Southern Lower Peninsula Michigan is in a perfect storm of whitetail deer problems, and hunters, farmers, resource managers and others are working together closely to remedy the issue. The hunter-farmer relationship, which used to be contentious over land access, is now partnering harmoniously. To salvage their agricultural livelihoods, farmers are welcoming hunters onto their properties to hunt the deer feeding off their crops. In conjunction with state species management officials, programs are being developed that address the No. 1 stumbling block for new hunters: mentors. Regional resource managers are collaborating, sharing their emergency deer management programs with each other. The deer population stands to benefit from the increased harvest since the current competition for food is leaving them weak, stunted and subjected to disease.

A cascade of events triggered the current deer management emergency in the Lower Peninsula, and it all stems from a decline in hunters. According to the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, since 1995 the number of registered hunters in the Mitten State decreased approximately 32 percent, from 800,000 to 600,000. Fewer hunters harvest fewer deer. In 2022, 303,081 deer were taken; in 2023 that number dropped to 274,299. This year, a similar number is expected. As of Click on Detroit’s Dec. 23 report, the take was at 271,432.

Taking advantage of the hunting reprieve, the whitetail population exploded. Deer eat entire fields of crops. In addition, Michigan is the fourth most likely state in which to hit a deer. On average, 306 vehicular deer strikes occur—a day—in Michigan in November during the rut. In 2023, 58,806 deer strikes occurred with 11 people killed and 1,633 injured. The prior year the number was 58,984, which represented a 13 percent increase over the 52,218 strikes in 2021. Finally, you have deer showing up outside their traditional ranges. A Click On Detroit video showed a deer entering a retail store and crashing into a display in panic. Along the bottom of the video were the words, “Too Many Deer, Not Enough Hunters.” According to the Michigan Office of Highway Safety Planning, Oakland County, just northwest of Detroit, is a deer-strike hotspot.

Farmington Hills is a well-to-do city about 22 miles northwest of downtown Detroit. You know you have a deer overpopulation emergency when one of the top reasons for concern is landscape destruction and blight. Of course, death and injury from crashes and increased incidence of Lyme disease for both humans and pets made the list, but blight is indicative of total vegetative devastation. The deer consume so much that the flora balance is disrupted, leaving the remainder subject to mildews, rusts and other rot. Police took more than 200 calls and untold emails regarding deer issues, including close to 600 complaints of injured or dead deer on private property—all within a three-year period. The number of dead dear picked up by the Farmington Hills Department of Public Works in a year doubled from 2014 to 2021, from 53 to approximately 100, respectively. The city’s aerial survey in 2016 counted 304 deer and by 2021, when the city presented its report to the public, the number had more than doubled to 729.

A positive outcome of the situation is a genuine desire for all parties to participate in the solution: local, regional and state; public and private. For instance, the Farmington Hills deer management website makes its findings and programs public so that other communities can follow suit. The city, in turn, borrows from the best practices of other communities, such as Ann Arbor, East Lansing and Rochester Hills. One of the top programs developed requires the fully committed and motivated farming community to now open their lands to a segment of the hunting community that is just under the surface. One can sense that R3 efforts to recruit, retain and reactivate may have been slow to produce measurable results, but now seem poised to usher a new generation of hunters into the field—the only stumbling block being the challenge of finding mentors. A bright spot for wannabe hunters in the Wolverine State is the Hunt Michigan Collaborative National Deer Association Farm Tour.

The Hunt Michigan Collaborative consists of three prongs. The first consists of state wildlife biologists and managers devising a deer management plan. The second required the buy-in of non-government wildlife conservation organizations to address the concerns of farmers, landowners and urban business people. The third provided a single clearinghouse of information for the public and those interested in hunting.

First, the Michigan Natural Resources Commission and the Department of Natural Resources created a Deer Management Initiative to address three major concerns: the lack of access to private lands; the spread of diseases that diminished the experience for hunters and their mentees; and the severity of deer densities relative to habitat. Wildlife managers seek to keep the herd balanced and healthy. This helps contain diseases, which would increase hunter satisfaction. Hunters who harvest healthy animals are more likely to attract others into the ranks. Educating those hunters about legal, regulated hunting and the species and its management remains an ongoing objective. And finally, improving habitat is essential for restoring damage and providing ample sustenance.

The plan received backing and support from conservation and hunting organizations, such as Michigan United Conservation Clubs, Michigan National Deer Association, Michigan National Wild Turkey Federation and others. The R3 focus ended up precipitating a masterful program in the Farm Tour. Farmers establish rules for hunting their property, volunteer hunting mentors coordinate legal and regulated hunts on the farms with interested hunters, and hunters get access to land long off-limits and a chance to hunt large, healthy deer. (Managers prioritize the taking of does in an added effort to control numbers going forward.) The mentors pick up the hunters, take them to a temporary blind set up on the property and pick them up when they are successful—or cold. All licensing and regulations, plus farm rules, are followed.

Everyone benefits. The farmer can salvage his livelihood. He might be working a job in addition to farming and doesn’t have time to coordinate the hunters or involve himself in management efforts. Allowing access is an easy and obvious move to save his crops. The mentor is afforded the opportunity to pass on his or her extensive knowledge, and the eager but inexperienced hunter benefits by being paired with someone who will show him or her the ropes for a successful hunt. After the harvest—an intimidating factor for a new hunter—the mentor will help to coordinate the meat processing with an area deer processing service, or the hunter can opt to donate the meat to charity. The National Rifle Association, the NRA Hunters’ Leadership Forum and numerous U.S. governors continue to encourage wild game meat donation to those less fortunate if the hunter has surplus venison to share outside his or her own family.

E-mail your comments/questions about this site to:

[email protected]

Proudly supported by The NRA Foundation and Friends of NRA fundraising.